Week 3

Resources

Below is a table with links to resources. Icons in orange mean there is an available file link.

| Chapter | Topic | Slides | Annotated Slides | Recording |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Bayes’ Theorem | |||

| 7 | Random Variables | |||

| 8 | pmf’s and CDFs | |||

| 9 | Independence and Conditioning (Joint Distributions) |

For the slides, once they are opened, if you would like to print or save them as a PDF, the best way to do this is:

- Click on the icon with three horizontal bars on the bottom left of the browser.

- Click on “Tools” with the gear icon at the top of the sidebar.

- Click on “PDF Export Mode.”

- From there, you can print or save the PDF as you would normally from your internet browser.

On the Horizon

Biostatistics Group Mentoring Session: 10/12

- Let me know if you need an extension of HW 2 because of this

Class Exit Tickets

Additional Information

Announcements for 10/9

- Homework 1 solutions are posted!

Announcements for 10/11

- Homework 1 released! Here are some overarching notes:

- If you start with “the probability that …” you must end with a value between 0 and 1.

- If you start with “the percent chance…” then you can have a value between 0% and 100%

- \(P(A)\) is not the same as probability of A only. Event A can overlap with B and C, so we need to find the part of A that does not overlap with B and C

- Hence we get \(P(A \cap B^c \cap C^c)\)

- If you start with “the probability that …” you must end with a value between 0 and 1.

- Group advising tomorrow at 5pm in Vanport 515!

- If you can’t get in, you can also Slack me

- Rising Voices Retreat

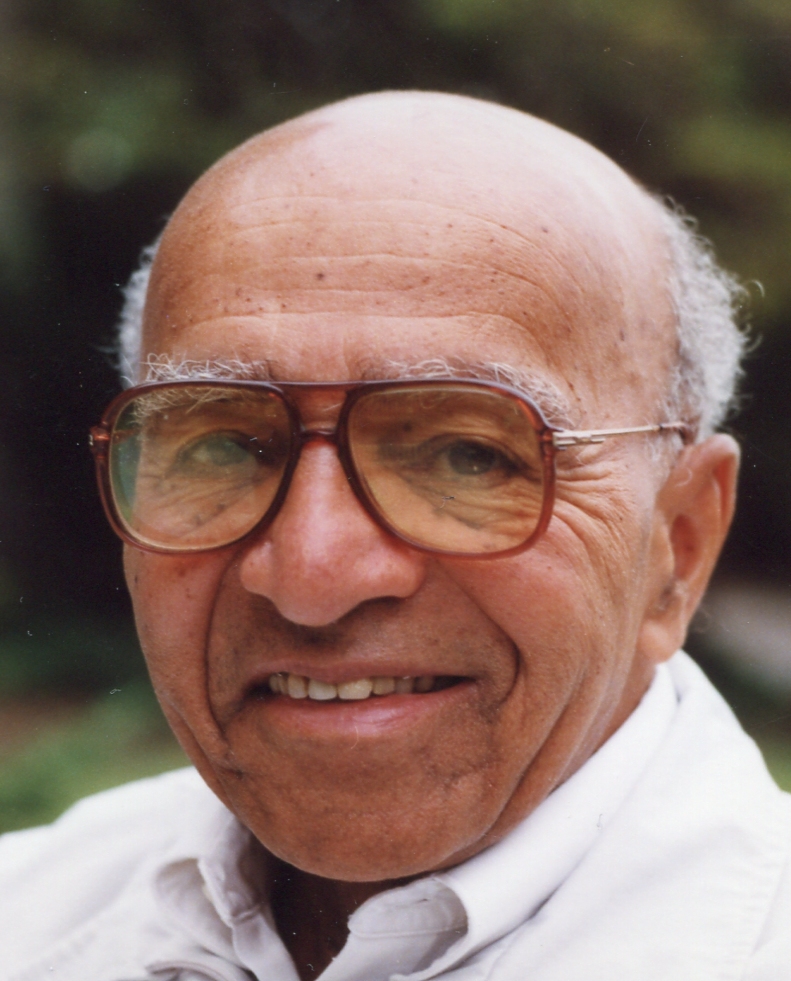

Statistician of the Week: David Blackwell

Blackwell was the first black person to receive a PhD in statistics (from University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in 1941 at the age of 22) in the US and the first black scholar to be admitted to the National Academy of Sciences. He was a statistician at UC Berkeley for more than 50 years. He was hired in 1954 after the department almost made him an offer in 1942 (but declined to do so when one faculty member’s wife said she didn’t want Blackwell hired because she wouldn’t feel comfortable having faculty events in her home with a black man). Hear Blackwell tell the story in his own words.

Topics covered

Blackwell contributed to game theory, probability theory, information science, and Bayesian statistics. The Rao-Blackwell theorem (you’ll likely see it in BSTA 551) is named after him.

Relevant work

- Blackwell, D. (1947). “Conditional expectation and unbiased sequential estimation”. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 18 (1): 105–110. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177730497.

Outside links

Please note the statisticians of the week are taken directly from the CURV project by Jo Hardin.

Muddiest Points

I am still working on these! Trying to go through them by end of day 10/11

1. Breast Cancer Example with Bayes Theorem

My apologies for not getting to this one. I encourage you to come to office hours if you would like to ask me directly. I think this youtube video might also help! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_c3xZvHto3k&ab_channel=OCLPhase2

2. Random Variables??

How are they functions? Why are they random? Why do we need them?

Basically quantifying the random outcome

- We can calculate probabilities more easily with RVs and we can use easier math notation

Still random because each value that the random variable takes is with a specific probability (not a certainty)

So the “random” part of random variable comes from the outcome in a random process and that randomness carries through to the RV

- Since the RV is a function of a random process: it is dependent on the probability space

So the function itself is deterministic, BUT each outcome of the function still holds a specific probability

The function part is essential for later manipulations of the RV

We will start taking derivatives and integrals of the RVs (especially important for continuous RVs)

Without a way to represent the probability as a overarching function, it is much harder to calculate derivatives and integrals

3. Why is is incorrect to say \(\omega \geq 5\) in our defined household random variable? And incorrect to say \(x \geq 5\) in the pmf? And why can we use inequalities, like \(3 \leq x < 4\), in our CDF?

Random variable part: \[X(\omega)= \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \omega & \quad \omega=1, 2, 3, 4\\ 5+ & \quad \omega = 5, 6, 7, ... \end{array} \right.\]

Why can’t we say \(\omega \geq 5\)? If values \(5, 6, 7, …\) are the only values greater than \(5\) that are defined in the sample space, doesn’t \(\omega \geq 5\) mean the same thing as \(\omega = 5, 6, 7, ...\)?

- Basically, we are using \(\omega\) to define the sample space. We don’t really have another way to communicate the sample space, so even though in our heads we know that \(\omega=5, 6, 7, …\) we need to make sure anyone we try to communicate will also understand this. \(\omega \geq 5\) does not convey that sample space to anyone looking at our math work.

Here is the pmf for our household example: \[p_X(x)= \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 0.28 & \quad x = 1\\ 0.35 & \quad x = 2\\ 0.15 & \quad x = 3\\ 0.13 & \quad x = 4\\ 0.09 & \quad x = 5+ \\ 0 & \quad \text{otherwise} \end{array} \right.\]

- When it comes to the pmf, we cannot use \(x \geq 5\) or \(1 \leq x < 2\) instead of \(x=5+\) or \(x=1\) because \(x \geq 5\) and \(1 \leq x < 2\) implies values like \(x=1.3\) and \(x=200.01\) will have a non-zero probability. Both of those values are included in the “otherwise” portion of the pmf, and have a probability of \(0\).

Here is the CDF for our household example: \[F_X(x)= \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 0 & \quad x < 1\\ 0.28 & \quad 1 \leq x < 2\\ 0.63 & \quad 2 \leq x < 3\\ 0.78 & \quad 3 \leq x < 4\\ 0.91 & \quad 4 \leq x < 5 \\ 1 & \quad x \geq 5 \end{array} \right.\]

- For the CDF, when we calculate \(F_X(x=1.3)\), for a discrete RV, there is no difference between \(F_X(x=1.3)\) and \(F_X(x=1)\). \(F_X(x=1)\) certainly feels more appropriate because \(x=1\) and \(p_X(1)\) is explicitly defined in our pmf. However, \(p_X(1.3)\) is also defined in our pmf. It falls under the “otherwise” category. Thus, \(p_X(1.3) = 0\) and for every value \(1 < x < 2\) the probability is \(0\). So for \(1 < x < 2\), there is no additional probability added into the CDF. Thus, \(F_X(x)\) for \(1 < x < 2\) is the same as \(F_X(1) = 0.28\).

4. What is CDF? And what is it good for?

What is the purpose of the CDF?

One purpose of the CDF is to calculate the probability of intervals of \(x\). For example, if we want to calculate the probability that some random variable \(x\) is between 30 and 35, we can say the probability is \(P(30 \leq x \leq 35)\). An easy way to calculate this is to find the difference between the two CDFs (\(F_X(35) - F_X(30)\)). We’ll see more about it in later chapters. It’s particularly helpful for continuous random variables.

The CDF starts to become very useful when we start discussing how certain we are of an observation (aka how much do we trust that an observation is coming from our prescribed distribution). Let’s say we tossed 50 fair coins. While the observation of 49 heads is possible, the probability is very small. And the probability that we get 49 or more heads is 0.000000000000045.

# Here I am using pbinom() to calculate the cumulative probability that I toss 49 # or more heads (q = 48) out of the 50 coins I tossed (size = 50) when the # probability of heads is 0.5 (prob = 0.5). pbinom() automatically calculates # the probability that we have 49 or less heads, so the "lower.tail = F" gives # us the probability that we get 49 or more heads. pbinom(q = 48, size = 50, prob = 0.5, lower.tail = F)[1] 4.52971e-14- Why did I use

q=48instead ofq=49for \(49\) or more heads. If you type?dbinomin your console in R, a Help tab will open. It will tell you that whenlower.tail=Fwe are calculating \(P(X>x)\), but we want the probability to include \(49\), so we put \(48\). Note, this will be different when we get to continuous functions.

- Why did I use

This probability may lead us to question whether the observed 49 heads really came from a fair coin. Maybe the probability that any given toss lands on heads is 0.99. What would the probability of 49 or more heads be then?

# Here I am using pbinom() to calculate the cumulative probability that I toss 49 # or more heads (q = 48) out of the 50 coins I tossed (size = 50) when the # probability of heads is 0.99 (prob = 0.99). pbinom(q = 48, size = 50, prob = 0.99, lower.tail = F)[1] 0.9105647Now the probability of getting 49 or more heads is 0.91. Pretty high! And I might be more inclined to believe my observation was from this unfair coin.

The cumulative probability gives us a sense of where in the distribution does an observation (like 49 heads) fall. Is it on the fringe? Or more centered within the probability density? This will definitely be clearer when we discuss continuous RVs.

What does it mean if the CDF is 1?

For example, in the household problem the CDF for 5 or more individuals is 1 (\(F_x(5+)=1\)). This means the probability that households have \(5+\) individuals or less (so the probability that a household has 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5+ individuals) is 1.

5. What’s up with the subtle changes in notation?

What’s the difference between \(X(\omega)\) and \(x\)?

In class we defined \(X(\omega) = x\). We call \(X(\omega)\) or \(X\) the random variable and \(x\) the realized value of that random variable.

For example: If I roll 20 dice, what is the number of dice that come up with 6?

\(X\) (or \(X(\omega)\)) is the number of 6’s that come up

\(x\) is the realized value (like 4 dice have 6’s) that can be observed

The number of 6’s (\(X\) or \(X(\omega)\)) is not yet a realized value, but it can be any of the realized values, \(x\)! Thus, we write \(X = x\).

I thought this Reddit thread is pretty helpful!